When listing the words that best describe the field of emergency medicine (EM), the following come to mind:

Intubations.

Ultrasounds.

Arterial lines.

Patagonia® vests.

Climbers.

Runners.

Dirtbags.

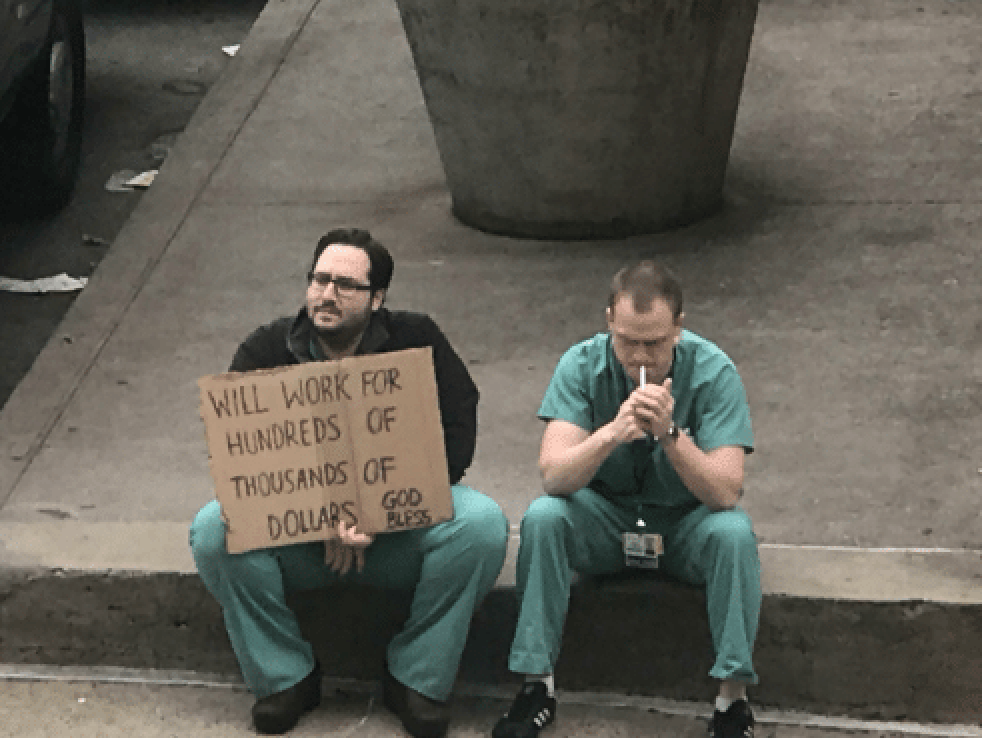

Unemployment?

While most of this list sounds like the elements of a fun Dr. Glaucomflecken sketch, the potential unemployment of emergency physicians has become the elephant in the proverbial hospital room.

EM is a highly popular specialty given the procedures, high acuity care, and balanced lifestyle; however, the looming threat of an unfavorable job market has emerged as a very possible reality over the last couple of years. This poses a conundrum for medical trainees, like ourselves, who are interested in this specialty, “is it worth it to go into EM, or will I graduate without a job and lots of debt?”

In April 2021, a task force made of different stakeholder groups in EM published the “EM Physician: Workforce of the Future,” which examined the supply and demand of emergency medicine providers over the next 10 years [1]. They concluded that “we are facing–for the first time in history–a likely oversupply of emergency medicine physicians in the next decade.” Specifically, they estimate that there will be a surplus of 9,413 EM physicians by 2030.

Although this surplus problem has been steadily rising over the last ten years, the COVID-19 pandemic helped accelerate the inevitable [1]. 2020 saw a dramatic decrease in total emergency department visits due to the pandemic. While there were just under 350,000 raw ED visits in January 2020, there were just under 200,000 raw ED visits by May 2020.

At its core, this workforce surplus is fueled both by the rising supply and falling demand of EM physicians. Why? Let’s get into it.

The Supply

The principal reason for the oversupply of emergency physicians is the increase in EM residency programs. Between 2012 and 2021 the number of accredited EM residency programs increased from 160 to 265 [2]. This means that while there were 1,762 EM residents in 2012, there were 2,571 EM residents in 2021 [1]. At the current rate of growth, there are predicted to be 3,097 EM residents by 2030, making EM one of the fastest-growing specialties. Furthermore, many of these new EM programs are associated with for-profit hospitals, rather than teaching hospitals. This does beg the question of whether hospitals are taking advantage of the cheaper labor provided by EM residents.

The Demand

As described above, ED visits plummeted in 2020. Since vaccinations have become widespread, ED volumes have returned to normal, but it will take years for the market to recover from last year’s losses. Still, the principal reason for the decreased demand is the rise in nurse practitioners and physician assistants (advanced practice providers [APPs]) working in the ED.* The number of APPs providing emergency care has doubled in the last decade, with the percentage of ED visits primarily staffed by APPs now reaching double digits [1]. To put this into perspective, there were 9,121 APPs providing EM services in 2012. With the current rate of growth, there are projected to be 24,332 APPs providing EM services by 2030. Taking the supply of emergency physicians into consideration, the task force predicts that there will be a demand of 49,637 emergency physicians by 2030, significantly lower than the supply of 59,050.

The Solutions

The task force proposed eight potential steps the field can take to prevent a catastrophic EM physician surplus [3]. Several solutions focus on reducing the number of EM residents. This includes standardizing all residencies to become four-year programs (currently a minority of residencies are four years), decreasing the number of residents in each program, and slowing the rate of new EM residency program approval. The prolific increase in APP care in the ED this century was also addressed, with recommendations against independent APP practice and instead suggesting that all APPs have in-person emergency physician supervision. In some healthcare systems, “supervision” for APPs is a loose term, as supervising physicians may not be on-site or even within 50 miles of the APP providing care. The third category of solutions focuses on expanding the reach of EM providers, both geographically and within the healthcare field. Last year, it was actually predicted that there would be a shortage of EM physicians in rural areas [4], and there is evidence of unmet emergency care demand in rural and underserved areas where additional infrastructure and healthcare facilities would be beneficial. Emergency physicians have always had the option to branch out into fields such as sports medicine, critical care, administration, public health, and more, but now career transitions such as these may be an important safety net for physicians struggling to find employment in an emergency department.

The bottom line? All hope is not lost for those considering going into EM. However, this field is not the same as it was even five years ago, where you could reasonably expect to find a job in an emergency department in whatever city you desired. For those of us running as far away from business school as possible by enrolling in medical school, it can be frustrating to have to consider how corporate interests have drastically shaped the EM job market. But other fields like anesthesiology have had similar existential crises and have found solutions. Of all medical fields, one with such an emphasis on adaptation, innovation, and preempting worst-case scenarios can be expected to recover from the less-than-ideal task force projections.

* The authors would like to acknowledge that they fully support and appreciate advanced practice providers. They are essential to any healthcare team and vital to our healthcare system. This article is meant to be objective in conveying why there is a surplus of emergency physicians and is not meant to endorse the removal of NPs/PAs from their respective positions.

- Rosenberg M. EM Physician – Workforce of the Future. ACEP. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/workforce/emphysicianworkforceofthefuture_4920.pdf. Presented March 9, 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021.

- Aintablian H. An Open Letter to the Specialty of Emergency Medicine. AAEM/RSA. https://www.aaemrsa.org/about/position-statements/specialty-of-em. Published April 10, 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021.

- ACEP Board of Directors. Workforce Considerations: ACEP’s Commitment to You and Emergency Medicine. ACEPNow. https://www.acepnow.com/article/workforce-considerations-aceps-commitment-to-you-and-emergency-medicine/. Published April 21, 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021.

- New Analysis Reveals Worsening Shortage of Emergency Physicians in Rural Areas. EmergencyPhysicians. https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/press-releases/2020/8-12-20-new-analysis-reveals-worsening-shortage-of-emergency-physicians-in-rural-areas. Published Aug 12, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021.