On August 1, 2018, the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) declared a new Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, located in the northeast region of the country [1]. By September 7, a total of 131 Ebola cases, including 90 deaths, had been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). Global response has included improved surveillance measures, increased vaccination efforts, and expansion of treatment facilities [2].

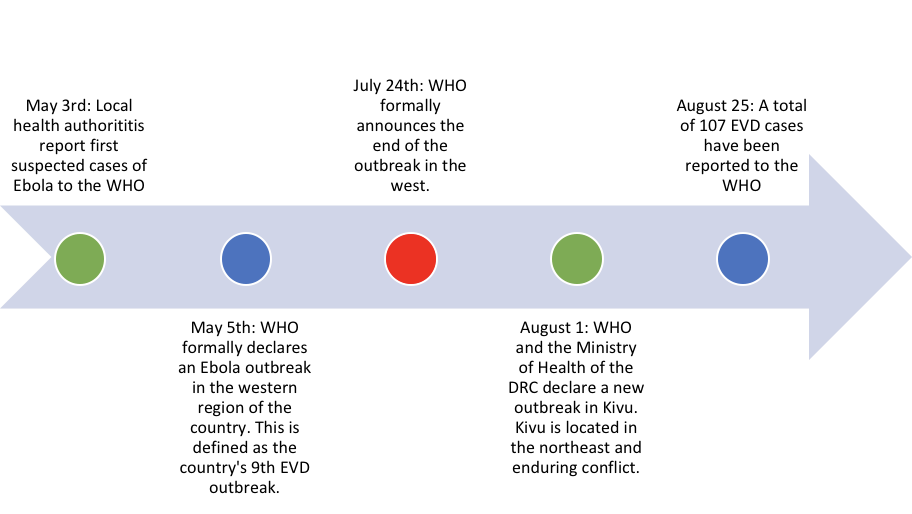

This announcement marked the start of the country’s second Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak this summer. The first outbreak began May 3, 2018 when local health authorities reported 21 cases of fever with signs of hemorrhage to the Ministry of Health. Five days later, the WHO confirmed the cases as EVD and formally declared an outbreak [3]. Between April 5 and July 24, a total of 54 cases of Ebola were confirmed. The WHO funneled $2 million USD from its emergency fund to contain the disease. Other major donors included the United States, the United Kingdom, and the World Bank. Overall, total funding to stop the spread of disease amounted to $63 million USD [4]. This price tag not only reveals the costliness in controlling an epidemic, but also the limited economic clout of the WHO.

On July 25, 2018 the WHO declared the end of the epidemic in western DRC and congratulated their partners for the success. For reference, the end of an outbreak is defined as two incubation periods—42 days in the case of Ebola—after the last confirmed patient has tested negative twice for the disease [4]. Only one week later, the disease cropped up again in the east, making it the tenth Ebola outbreak in the country’s history.

The story of Ebola in the DRC (previously known as Zaire) did not begin in 2018. In fact, it began in 1976 when a 42-year-old man presented with fever and chills to a local clinic [5]. He was treated for malaria with injections of chloroquinone and sent home. He returned to the clinic one week later with severe abdominal cramps and intestinal bleeding. Soon after, he died with a “hemorrhagic syndrome” from an “unknown cause.” Within the next month, the clinic reported dozens of cases of febrile hemorrhage, which have now been recognized as the entry of EVD into the human population.

Although the first Ebola outbreak in DRC occurred more than 40 years ago, it was not until the 2014-2016 outbreak in West Africa that global hysteria developed around the virus. Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) reported the first cases of Ebola from Guinea to the WHO, which the agency ignored [6]. The WHO’s delayed response to the 2014 outbreak has been recognized by global health experts as one of the greatest failures in the organization’s history. In her statement, then-Director General of the WHO Dr. Margret Chan, admitted that they did not have the capacity to “cope” with an emergency of that scale. She also included a resolution to establish a “Global Health Emergency Workforce” with earmarked funds to better respond to future outbreaks.

Ebola Timeline DRC (2018) [13]

How has the World Health Organization handled the current outbreak in the DRC?

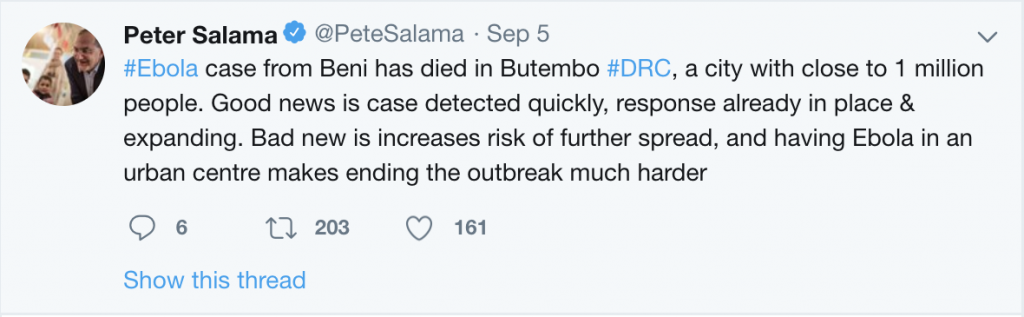

For the most part, under the leadership of Dr. Peter Salama, Deputy Director of the Emergency Preparedness and Response, the WHO has handled the crisis to the best of their ability. Their partnerships with non-governmental organizations like MSF have led to effective vaccine investigation, data management, and capacity building. However, controlling the outbreak has proven near impossible because of the context. On September 5, 2018, it was reported that an Ebola case was detected in the city of Butembo, which has a population close to one million. While the WHO and partners were quick to respond, there is a new fear that if the outbreak reaches a densely populated urban area, it will spread like wildfire [7].

Additionally, the northeastern region of the DRC faces a humanitarian crisis with the early hallmarks of an ethnic cleansing campaign against the Hema community [8]. Although the death toll remains unknown, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported the displacement of 48,105 people between December 2017 and March 2018. Many of these individuals have fled to neighboring Uganda; however, a greater number remain displaced in their own country. The total number of internally displaced people (IDPs) has reached one million [9].

Violence creates an environment amenable to the spread of disease, and Ebola has closely followed this pattern. In a press conference, Dr. Tedros, the newly elected Director General of the WHO, announced that the security threat makes the current outbreak in Kivu more dangerous than past outbreaks [10]. Red zones, or areas of active conflict, serve as hiding places for EVD. Not only do these areas remain inaccessible to healthcare workers, but infected individuals living in red zones are restricted from seeking medical care.

The Ebola epidemic in the DRC serves as a case study to the nuisances of treating infectious disease and global pandemic response. According to the WHO, health in conflict ranks as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2018 [11]. This past year alone, Yemen faced the largest cholera epidemic in modern history [10]. Additionally, the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar have faced numerous outbreak threats from influenza, diphtheria, and cholera [12]. Providing health in settings of violent conflict presents as a serious challenge because its efficacy depends on factors beyond the scope of medicine alone. Rather, it requires complex systems that integrate politics, human rights, and a strong public health infrastructure.

For updates on the Ebola Outbreak, please visit: http://www.who.int/ebola/situation-reports/drc-2018/en/

- World Health Organization. Ebola situation reports: Democratic Republic of the Congo. who.int. http://www.who.int/ebola/situation-reports/drc-2018/en/. Published August 28, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. who.int. http://www.who.int/entity/csr/don/24-august-2018-ebola-drc/en/. Published August 27, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2018.

- WHO Health Emergency Program. Ebola Virus Disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo. Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment, 25 July 2018; 17. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273348/SITREP_EVD_DRC_20180725-eng.pdf?ua=1. Published July 25, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Ebola outbreak in DRC ends: WHO calls for international efforts to stop other deadly outbreaks in the country. who.int. http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/24-07-2018-ebola-outbreak-in-drc-ends-who-calls-for-international-efforts-to-stop-other-deadly-outbreaks-in-the-country. Published July 24, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2018.

- Breman JG, Heymann DL, Lloyd G, et al. Discovery and Description of Ebola Zaire Virus in 1976 and Relevance to the West African Epidemic During 2013–2016. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;214(suppl 3). doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw207.

- McSpadden K. WHO Admits Failures in Response to Ebola Outbreak. Time. http://time.com/3827810/who-ebola-crisis-response-failure/. Published April 20, 2015. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- @PeteSalama. #Ebola case from Beni has died in Butembo #DRC, a city with close to 1 million people. Good news is case detected quickly, response already in place & expanding. Bad new is increases risk of further spread, and having Ebola in an urban centre makes ending the outbreak much harder. https://twitter.com/PeteSalama/status/1037347269878661121. Posted on September 5th, 2018

- Turse N. An ethnic cleansing campaign may be underway in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a VICE News investigation reveals. VICE News. https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/437zep/an-ethnic-cleansing-campaign-may-be-underway-in-the-democratic-republic-of-congo-a-vice-news-investigation-reveals. Published March 12, 2018. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- UN Live United Nations Web TV – WHO: Press Conference – Update on Ebola operations in DRC (Geneva, 14 August 2018). United Nations. http://webtv.un.org/The/watch/who-press-conference-update-on-ebola-operations-in-drc-geneva-14-august-2018/5821961745001/?term=. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- World Health Organization. 10 threats to global health in 2018 – World Health Organization. Medium. https://medium.com/@who/10-threats-to-global-health-in-2018-232daf0bbef3. Published February 9, 2018. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- Erikson A. 1 million people have contracted cholera in Yemen. You should be outraged. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/12/21/one-million-people-have-caught-cholera-in-yemen-you-should-be-outraged/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.f7f50c72f680. Published December 22, 2017. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Major outbreaks averted, thousands of lives saved; but Rohingyas continue to be vulnerable. who.int. http://www.searo.who.int/mediacentre/releases/2018/1694/en/. Published August 26, 2018. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Timeline of the Ebola outbreak response in Democratic Republic of the Congo. whot.int. http://www.who.int/ebola/drc-2018/timeline/en/. Published July 25, 2018. Accessed August 30, 2018.

Tina Samsamshariat is a member of the class of 2022 at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix. She received her Bachelor of Science from the University of California, Los Angeles and her MPH from the University of Southern California. She enjoys surfing, climbing, and rap music. Twitter: @TSamsamshariat