Within the past decade, player safety has become a priority within the National Football League (NFL). While the obvious reason for this is to avoid unnecessary injuries, there has become an increasing focus on the long-term consequences of the physical toll that football has on players after they retire. One of the more serious physical complications that has linked to football is chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease that is caused by repeated head injuries. Clinical symptoms include cognitive impairments (impaired memory and executive function), behavior abnormalities (aggression, paranoia, impulsivity), and mood disorders (depression, anxiety, suicidality) [1]. Onset of these symptoms occurs roughly 8-10 years after multiple mild traumatic brain injuries and presents in progressively worsening stages, making an early diagnosis of CTE difficult [2].

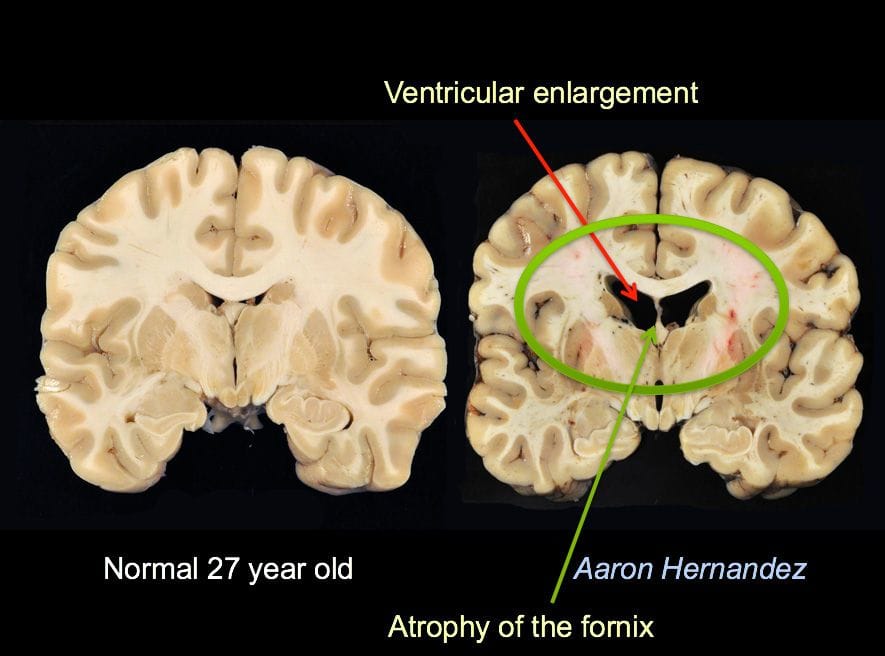

Similar to Alzheimer’s disease, CTE is a tauopathy, meaning it is characterized by the deposition of abnormal tau protein in the brain [3]. The distribution of the tau protein differs from Alzheimer’s disease in that tau proteins in CTE are primarily distributed in superficial cortical layers [4]. CTE also results in brain atrophy and decreased brain weight, with the greatest losses seen in the frontal and temporal cortices of the medial temporal lobe [2].

In the professional sporting world, there were cases as early as in the 1920s in boxing, described as “punch drunk” and later dementia pugilistica, where boxers were being seen with confusion, tremors, and difficulty speaking [5]. As years passed and research expanded, these findings were not confined just to boxing and were also seen in other contact sports such as wrestling, ice hockey, and football.

In the early 1990s, multiple NFL former players claimed that they were suffering from post-traumatic migraines from concussions that were not properly treated. This resulted in the formation of the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee (mTBI) [6]. In 2005, Omalu et. al [7] published the case of Mike Webster, the first former NFL player diagnosed with CTE. Webster, who had suffered from amnesia, depression, and dementia in his post-playing days, had a brain that was similar to the boxers who had been diagnosed with dementia pugilistica during his autopsy. These findings went relatively ignored until 2010, when a report was released that Chris Henry, a wide receiver who had died a year prior in a car accident at the age of 26, was found to have CTE on an autopsy. Henry’s autopsy findings were taken seriously given that he was the first active player to be diagnosed with CTE and that he had never been diagnosed with a concussion in his five seasons in the NFL or during his college career at West Virginia University. The concern was that numerous, lesser blows to the head could lead to CTE in addition to severe helmet-to-helmet hits.

More recently, Hall of Fame linebacker Junior Seau’s autopsy showed definitive signs of CTE, less than a year after he was found dead due a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. Those close to Seau had stated that in the years leading up to his death he had been experiencing mood swings, depression, forgetfulness, and detachment. Convicted murderer and former Patriots tight end and Aaron Hernandez was found to have stage 3 (out of 4) CTE in his autopsy. Hernandez was 27 years old and stage 3 CTE had never been seen in someone less than 46 years old, according to Ann McKee, head of Boston University’s CTE Center.

Aaron Hernandez’s brain

Photo from Boston University School of Medicine

The link between football and CTE has become increasingly apparent, especially after a study showed 110 out of 111 deceased former NFL players had a neuropathological diagnosis of CTE at their autopsy [8]. In 2009, the NFL implemented a standardized five-step concussion protocol, which has been modified almost yearly and now employs unaffiliated neurological consultants to assess players on the sideline. In 2018, the NFL approved a 15-yard penalty for helmet-to-helmet contact as well as a potential ejection. These changes, along with stricter helmet regulations, have contributed to a lower concussion rate, decreased from 281 in 2017 to 224 in 2019.

Additionally, a recent study showed that a group of former NFL players with cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms had higher tau levels on positron emission tomography (PET) scans in the bilateral superior frontal, medial temporal, and left parietal regions of the brain compared to controls [9]. These regions are often affected in CTE, showing promise that the disease could be detected earlier than an autopsy.

While the NFL has worked to limit concussions and brain injuries, an important key to combating CTE may be to make changes early on. The aforementioned study also found that in 48 of 53 (91%) college football players and 3 of 14 (21%) high school football players, some form of CTE was seen on an autopsy [8]. Dr. Javier Cárdenas—neurologist and director of Barrow Neurological Institute’s Concussion center—has created the Barrow Concussion Network to provide concussion education and coverage for Arizona high school games. Athletic trainers can use a Skype-like tool to reach concussion specialists during games. Cárdenas, who is also on the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee, also created the Barrow Brainbook, which teaches high school students about concussions and requires that they pass a test prior to be cleared to play.

As research further advances our knowledge of CTE, it is clear that the issue of long-term brain damage is not strictly limited to the NFL. Fortunately, various organizations and providers have taken notice of this and have begun to implement strategies to limit the amount of traumatic brain injuries in football. Hopefully, this work can reduce the number of concussions in contact sports and prevent CTE early on.

[1] Asken BM, Sullan MJ, Dekosky ST, Jaffee MS, Bauer RM. Research Gaps and Controversies in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. JAMA Neurology. 2017;74(10):1255.

[2] McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, et al. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy After Repetitive Head Injury. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2009;68(7):709-735.

[3] Kovacs GG. Tauopathies. Handbook of Clinical Neurology Neuropathology. 2018;145:355-368.

[4] Jordan BD. The clinical spectrum of sport-related traumatic brain injury. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2013;9(4):222-230.

[5] Castellani RJ, Perry G. Dementia Pugilistica Revisited. Journal of Alzheimers Disease. 2017;60(4):1209-1221.

[6] Solomon G. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in sports: a historical and narrative review. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2018;43(4):279-311.

[7] Omalu BI, Dekosky ST, Minster RL, Kamboh MI, Hamilton RL, Wecht CH. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(1):128-134.

[8] Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, et al. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA. 2017;318(4):360–370.

[9] Stern RA, Adler CH, Chen K, et al. Tau Positron-Emission Tomography in Former National Football League Players. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(18):1716-1725.

Roy Bisht is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, Class of 2021. He is from the Bay Area and graduated from the University of California, Irvine in 2016 with a degree in Biological Sciences. His interests include baseball, football, longboarding, and collecting sneakers.