Working in a medical profession almost invariably means having to confront human mortality. Though death is ultimately inevitable, in many situations physicians can experience patients’ deaths as a failure on their part to provide appropriate care. It is only in the past several decades that palliative and hospice models of care have emerged, acknowledging that casting death as an enemy to be avoided at all costs can detract from patient care.

Ethical medical practice requires working with patients to understand their goals in end of life care and working with them to enhance their autonomy and well-being as they undergo the often frightening but ultimately universal experience of dying. A deeper understanding of the medical ethics of death and dying can be developed by considering how humans have historically experienced mortality. This article presents a brief history of death and dying in Western cultures.

Notably, death and dying have only recently been considered primarily in a medical context. The transition to a medical approach to dying and death is closely linked to both the expanded role of medicine in the past few centuries as well as with the ways in which medical knowledge has changed the actual process of dying. Those living in Westernized countries in the modern era primarily associate death with old age, with death due to accidents or maladies occurring earlier in life considered premature. This is consistent with the modern experience of death, with the vast majority of deaths occurring after the age of 65 [1]. Historically, however, death from old age was not a common experience. Sixteenth-century philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote “to die of old age is a death rare, extraordinary, and singular, and therefore so much less natural than the others: it is the last and most extreme sort of dying” [2].

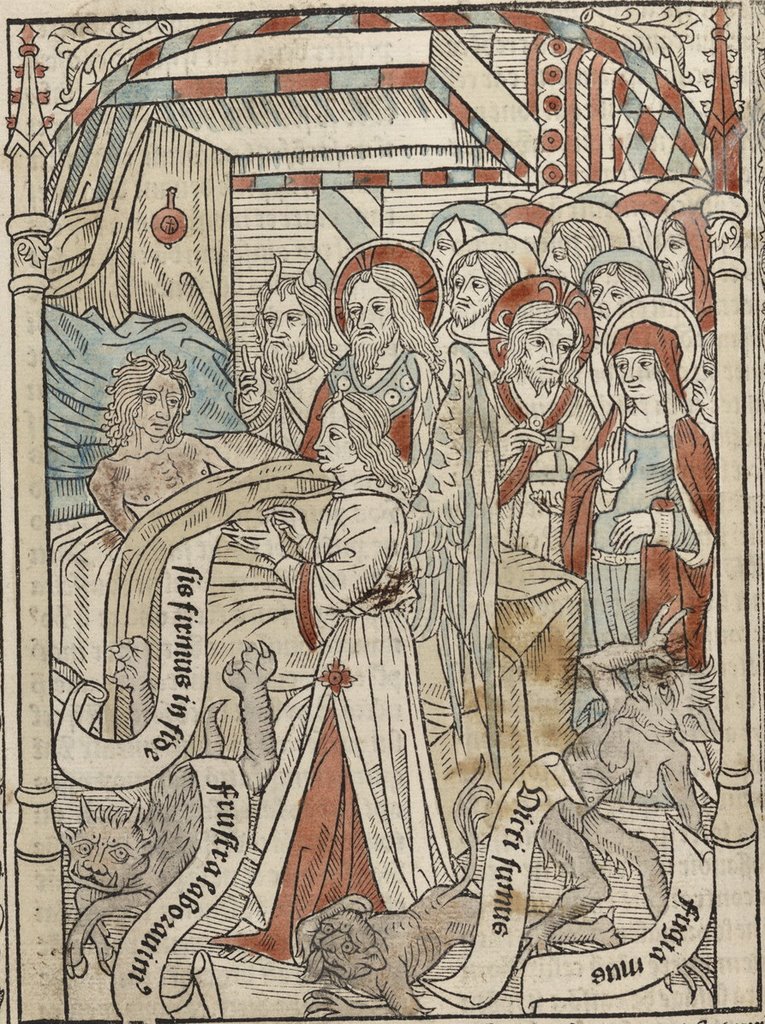

For the majority of human history, the process of death was primarily under the jurisdiction of religious institutions and beliefs [3], and death was typically a swift process that could occur at any age [4]. In medieval Europe, norms for dying well were prescribed by popular Latin texts about ars moriendi, the art of dying. In Abrahamic religions, death is conceived of as a transition from this life to an afterlife. European Christians considered the way in which a person died to be important for the determination of whether or not an individual would go to heaven or hell. Acceptance of death, renunciation of worldly concerns, affirmation of one’s faith, and hope for God’s forgiveness for sins were all important for dying well [3][4]. For Catholics, a final confession and Eucharist were essential. Struggles and suffering associated with death were construed as representative of the struggle between good and evil, wherein the Devil tempts the dying person to cling to life. While rituals surrounding death provided some degree of physical comfort, their primary purpose was preparing the soul for its journey to the afterlife [5].

Prior to the modern era, death from sickness and aging typically occurred in the home or in hospitals that functioned as almshouses. For people who survived into old age, the extended family or the nuclear family ensured that the elderly were cared for. In many Western societies, this meant that some children would remain in the parental home before leaving to begin their own family until their parents died. It was not until after World War II that a majority of the population died outside of the home [4]. Early hospitals or almshouses were the norm for individuals who did not have family to care for them. Early hospitals were primarily Christian institutions. While they served the social function of segregating the sick from the general population, prior to the Renaissance they prioritized the provision of “shelter, food, clothing, and moral rehabilitation” over the provision of early, and typically ineffective, medical services [5]. Physical recovery became a greater priority for hospitals during the Renaissance, in large part due to an increase in the prioritization of maintaining a population of “productive members of society” [5]. During this time period, hospitals came to rely more heavily on funding from local governments [5].

Over the course of the medicalization of the hospital, doctors became closely involved in death rituals. By the 1700s, thanks in large part to Enlightenment thinking, medical science was growing to have greater social authority. Roy Porter, author of The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity, describes doctors as coming to replace the role of the priest in death ceremonies, easing the dying process through the use of opiate cocktails [3]. While the majority of deaths still occurred in the home, almshouses remained the norm for the poor sick and elderly without familial support; however, the almshouse and the hospital came to have separate roles, with hospitals posited as places of recovery, as well as teaching and research. In order to artificially reduce hospital mortality rates, many hospitals would discharge dying patients early to avoid including their deaths in the hospital’s records. Other patients would voluntarily leave to die at home. For those who could not go home, the traditional hospice role of the hospital was relegated to the now entirely separate institution of the almshouse [5].

According to Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal, by the early 1900s in the U.S., the almshouse, or poorhouse, was typically an institution that incarcerated the poor elderly alongside “out-of-luck immigrants, young drunks, [and] the mentally ill” [4]. Poorhouses were marked by their filthy conditions and dehumanization of their “inmates,” who were generally put to work for their apparent moral failings. Protests during the Great Depression prompted the establishment of Social Security, which enabled the elderly to maintain financial stability in retirement, but this had little effect on the prevalence of poorhouses as the disability and infirmity encountered in old age typically preclude independent living. Hospitals were once again tasked with caring for the dying, but the 1950s-hospital found itself unable to meet the needs of dying patients. In order to clear out hospital beds, they petitioned for help from the government. Early nursing homes were established using federal funds allotted in 1954 to build custodial units for patients in need of “extended recoveries” [4].

The establishment of the nursing home did not result in the reduction of deaths occurring in hospitals; in-patient deaths reached a peak in 1980, with 54 to 60% of deaths occurring among patients admitted to the hospital [5]. Scholars argue that this trend is the result of an emergent cultural reluctance to avoid frank discussion of inevitable death, which was in part a result of the medical institution’s interpretation of a patient’s death as a failure to save a life [3][5][6]. Rather, medical practitioners sought to do everything in their power to cure underlying diseases. The development of life support systems provided technological solutions to artificially perpetuating the life of “dead” people [3].

The hospice movement largely emerged as a reaction to concerns about the hospital approach to death. This includes both concerns with the inadequate treatment of terminally ill patients and concerns over the expenses associated with the unrelenting use of life-extending medical technologies. Cicely Saunders, a British nurse, is credited with establishing the first modern hospice, St. Christopher’s Hospice in London, in 1967 [3], and the movement would begin to be embraced in the U.S. in the 1970s [5]. The hospice philosophy is often positioned as a modern ars moriendi, as it prioritizes enabling a “good death” over the prolongation of life at all costs [3][4]. The tenets of hospice care uphold a holistic vision of meeting a patient’s physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual needs [7]. Notably, the hospice model does not eschew medical technology; pain relief, for example, is typically provided through morphine or other opiates. While hospice facilities exist, many hospice programs enable death in the home, which has resulted in a decrease in deaths in the hospital [4][5]. Palliative medicine and gerontology are other medical specialties that challenge the medical desire to extend life at all costs [4]. Although hospice care, palliative care, and gerontology have grown in prevalence, there are no dedicated board examinations for these specialties.

Alternative reactions to the modern hospital’s inability to effectively care for the dying are the assisted death and euthanasia movements [3]. Several laws legalizing assisted death have been passed by several governments, including certain states in the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland [8][9]. Many of the laws legalizing assisted death are physician-assisted death laws, wherein a doctor is allowed to prescribe a mentally competent, terminally ill patient a pill that causes swift, painless death. The Swiss model is slightly different than most other assisted death models in that assisted death is legal due to an omission in the penal law, which stems from Swiss traditions of assisted death. The Swiss model is not a physician-assisted death model as other individuals, including lay volunteers, are permitted to provide assistance in death. Those being assisted are also not necessarily limited to the terminally ill [9].

Interestingly, palliative care practitioners are often unreceptive or antagonistic to assisted death legalization. Palliative practitioners opposing assisted death argue that an ethical difference exists between allowing the removal of technologies that allow the perpetuation of life and providing a pill designed to hasten death. They also indicate that palliative care is capable of reducing suffering at the end of life, obviating the need for assisted death, and that establishing services for assisted death would divert resources from palliative approaches [8]. Notably, in the Netherlands, where a system of assisted death has existed for years, palliative care programs have developed slowly in comparison to other Western countries. Gawande argues that reliance on assisted death measures—one in 35 Dutch seek assisted death at the end of their life—can prevent full consideration of the possibilities of the good death palliative and hospice care seek to provide [4].

Death and dying will undoubtedly remain ethically and existentially difficult issues for medical providers. The trend of the past few decades has been one of establishing a new ars moriendi, with care provided by an interdisciplinary team and the goal of helping patients achieve a “good death,” whatever that may mean to them personally. Acceptance of death as inevitability—but still a process that medical professionals can help with in some way—seems to generally improve patient’s well being during the end of life. However, differences in opinion about what constitutes a good death abound, and this topic is likely to continue to be a source of challenges as medicine and our perceptions of death and dying continue to evolve.

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, & Tejada-Vera B. National Vital Statistics Report — Deaths: Final Data for 2014. CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. 2016; 65(4): 1.

- de Montaigne M. Of Age. 1576. Retrieved from http://www.laphamsquarterly.org/conversations/mimnermus-montaigne.

- Porter R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1998.

- Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014.

- Risse GB, & Balboni MJ. Shifting Hospital-Hospice Boundaries: Historical Perspectives on the Institutional Care of the Dying. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2013; 30(4), 325-330.

- Sadler JZ, Jotterand F, Lee SC, & Inrig S. Can Medicalization be Good? Situating Medicalization within Bioethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. 2009; 30(6), 411-425.

- Floriani CA, & Schramm FR. Routinization and Medicalization of Palliative Care: Losses, Gains and Challenges. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2012; 10(4), 295.

- Karsoho H, Fishman JR, Wright DK, & Macdonald ME. Suffering and Medicalization at the End of life: The Case of Physician-Assisted Dying. Social Science & Medicine. 2016; 170, 188-196.

- Ziegler SJ. Collaborated Death: An Exploration of the Swiss Model of Assisted Suicide for Its Potential to Enhance Oversight and Demedicalize the Dying Process. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2009.

Michelle Arnold is member of the The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Class of 2022. She received her Bachelor’s degrees in Biochemistry and Spanish from Arizona State University in 2015 and a Master’s degree in Applied Ethics and the Professions (Biomedical and Health Ethics) also from Arizona State University in 2017. She has interests in medical humanities, patient-provider relationships, and improving healthcare for underserved communities.