With the Medicare Access and Chip Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) about to take effect next January, only half of US physicians report being familiar with the impending legislation [1]. While some are aware that the traditional fee-for-service model of healthcare is coming to an end, not many understand the specifics of the value-based system that will replace it. MACRA will change our healthcare system by fundamentally altering how providers are paid; instead of being reimbursed for simply providing medical care, payments to doctors and hospitals will be tied to their ability to keep patients healthy and take necessary actions to improve our healthcare system. More specifically, the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS)—one of the two payment tracks that providers can choose between under MACRA—will measure physicians’ performance on a defined set of criteria and adjust their Medicare Part B payments accordingly. While high-performing physicians may see a substantial boost in income, others may experience significant reductions.

In order to understand the financial implications of MIPS for doctors, we first have to be familiar with the performance categories that they will be assessed on. These metrics, in the end, will affect their Medicare payment adjustments. The performance categories include:

• Quality – as most healthcare professionals already know, MIPS will adjust physician reimbursement rates based on the quality of care provided in the clinic and operating room. This will be measured by six quality metrics, which doctors can choose at their own discretion based on their specialty and practice type. These metrics will be supplemented by 2-3 population-based health measures chosen by CMS.

• Advanced care information (ACI) – an update of Meaningful Use (MU), which will track doctors’ implementation of health information technologies in their practices.

• Clinical practice improvement activities (CPIA) – will measure the ability of physicians to improve their practices in the areas of care coordination, patient engagement and patient safety. Doctors will be able to select their performance measures in nine categories, including goals such as achieving health equity, integrating behavior and mental health, and improving patient engagement, among others.

• Cost – doctors will also be assessed on more than 40 different cost metrics which measure their use of financial resources in providing medical care. Fortunately, CMS will calculate these scores using Medicare claims and will require no additional work for physicians [2-3].

Within each category, the performance metrics for a given doctor will be compared to the performance of her peers. This is then summed into a categorical score (e.g., an overall score for quality), which is then weighted. The weighted averages of the four categorical scores are then summed to yield a composite performance score (CPS), which can range from 0 to 100. This, ultimately, will determine the adjustments of a doctor’s Medicare Part B payments.

A low-performing doctor, hypothetically with a CPS = 0, will see a 4% reduction in her Medicare reimbursements in 2017. By 2020, this penalty increases to 9%. A high-performing doctor, with a CPS = 100, will see additional incentive payments of 4% and 9% in 2017 and 2020, respectively. The majority of physicians will, of course, fall within this range and see a corresponding gradation in penalties and incentives. By law, MACRA must remain revenue-neutral, meaning that the dollar value of penalties for doctors across the U.S. must equal the dollar value of incentive payments. Since it is possible that total penalties exceed total incentives, high-performing doctors may receive a multiple of their incentive payment, denoted as X (which is legally capped at X = 3). This essentially means that high-performing doctors benefit significantly if their peers have poor CPS grades because their 4% payment incentive could theoretically jump to 12% in 2017 (if X = 3). Additionally, providers in the top 30% of their cohort will receive a 10% “exceptional performance bonus” [2].

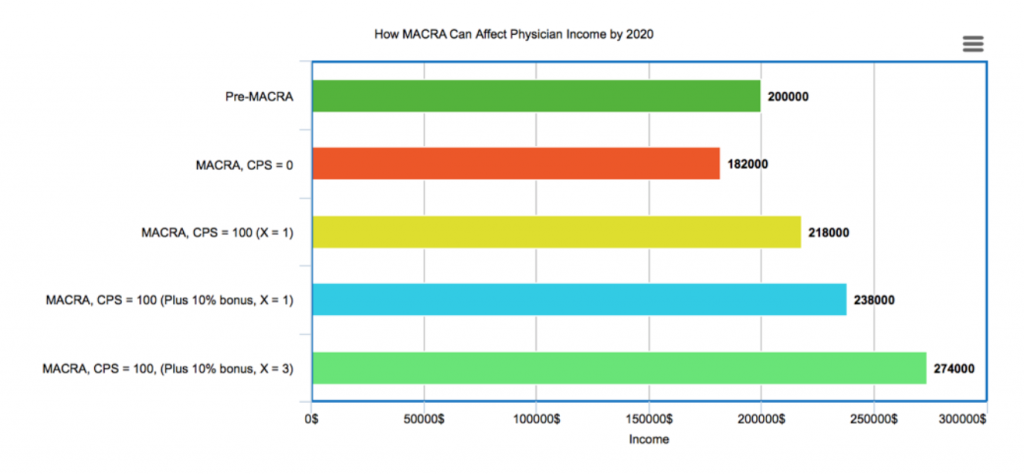

Displayed below is a theoretical example of how different CPS scores could affect the 2020 income (the year when incentives and penalties reach their peak) of a doctor who earned $200,000 pre-MACRA.

This hypothetical physician, under MIPS, could see her income range from $182,000 (CPS = 0) all the way to $274,000 (CPS = 100, plus 10% bonus, X = 3). It is important to note that specialists with higher incomes would see an even wider range of incomes under MIPS. The bottom line: the new payment system will substantially increase the incomes of physicians that are able to align their practices with this new model of healthcare; however, it will be at the expense of those that are not quite as adept.

In addition to its financial impact on physicians, MIPS will have two significant effects on the organization and culture of medicine. First, as insurers follow CMS’s lead in the transition to performance-based reimbursement, nearly all of a physician’s income (not just Medicare Part B payments) will be tied to their ability to provide better healthcare. This has been modeled in the previous calculations. The increased complexity of practicing medicine and the financial risk now associated with it will substantially fuel the transition from private practice to physician employment by large hospital systems that have the infrastructure to succeed in the new MACRA environment. Second, the significantly increased competition among physicians to produce better outcomes than their peers may diminish camaraderie amongst doctors. When incomes are tied to outperforming their peers, doctors may choose not to share new surgical techniques, novel medical approaches, or more efficient business operations changes that they have discovered because doing so would diminish their competitive advantage. While the exact implications of any legislation as far-reaching as MACRA can never be fully anticipated, we can expect significant changes in not only physician income but also radical transitions in the broader US healthcare landscape.

Jason Paul Singh is a student at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, class of 2020. He graduated summa cum laude from the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor with a BS in economics. His academic interests include alternative healthcare models and methods to improve efficiency in medicine. In his spare time, Jason enjoys traveling, reading and running. Please feel free to contact him at jpsingh[at]email.arizona.edu with any questions or comments.