COVID-19 has left brutal impacts on the US healthcare system and economy, as well as many other fronts. As of this month in the US, there are approximately 3 million confirmed cases with a total death count of nearly 130,000 [1]. In economic terms, the country has witnessed record unemployment rates as a direct result of the pandemic. During a two-week window in March, almost 10 million people filed for unemployment, and in April, a record high unemployment rate of 14.7% was documented [2,3]. COVID is marching the US into a recession. Historically, the US has generally had successful post-recession recoveries. But could this recession be different? And what are the implications on the healthcare economy specifically?

The healthcare sector has not taken many significant hits during previous recessions. This is likely due to the very nature of human illness as the demand for health care is relatively stable—it does not fluctuate with the business cycle as many other sectors do. But COVID-19 has prominently changed this relationship.

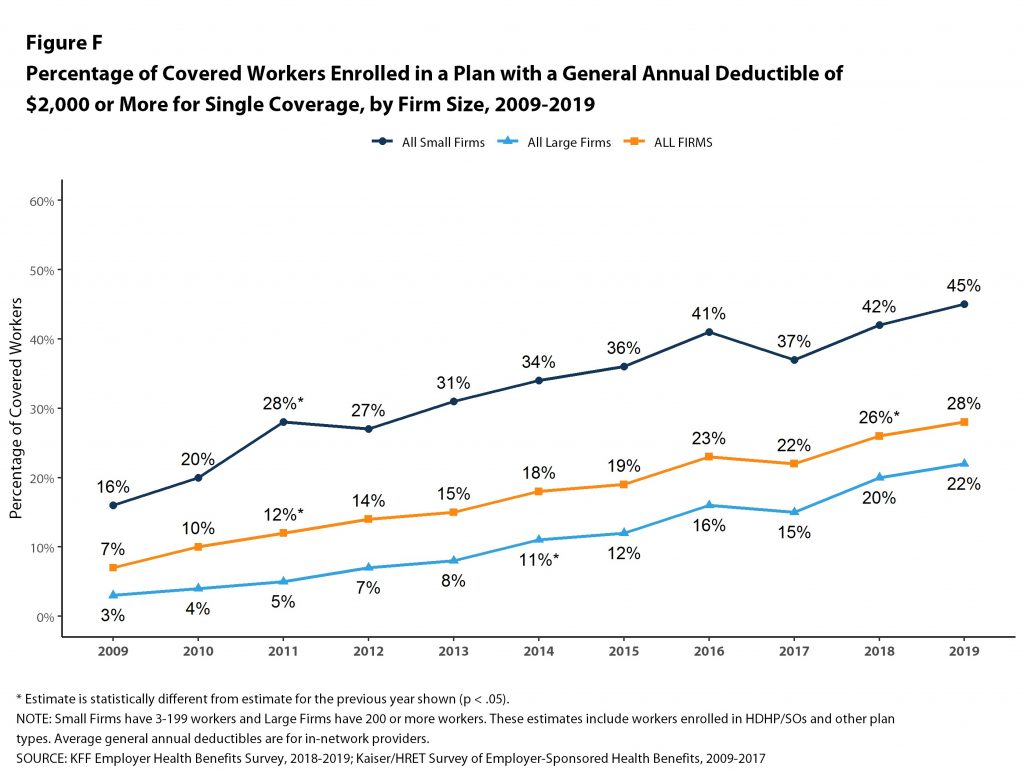

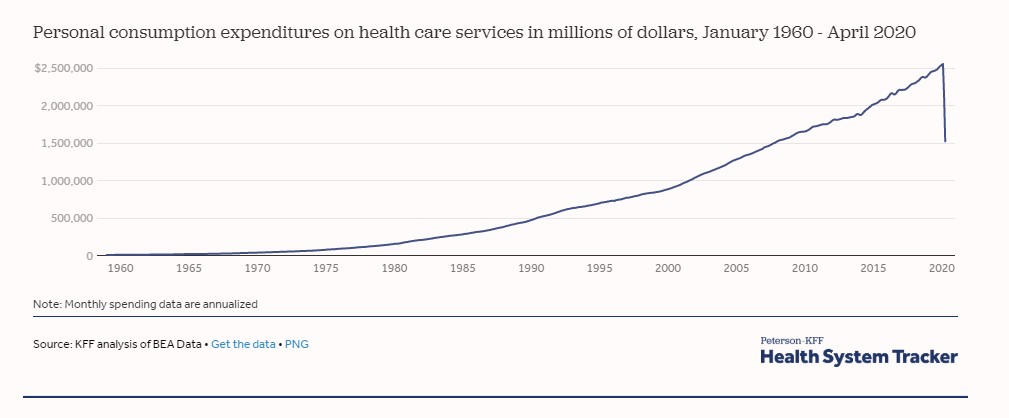

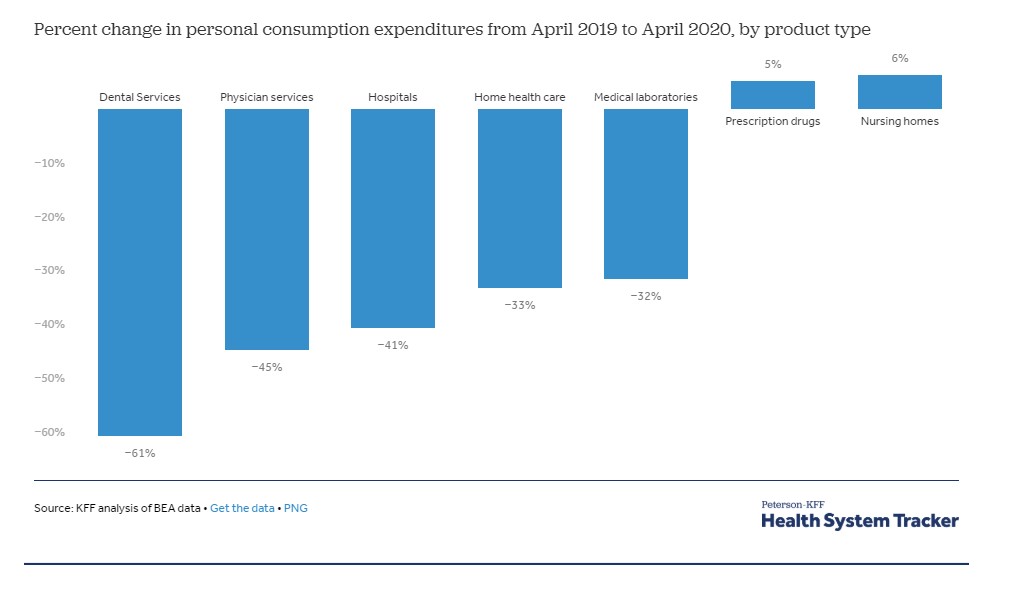

From the perspective of the patient, society has been in a quarantined state. Most individuals are not engaging in many normal daily activities. This includes the use of medical services, as regular health visits have experienced a stark drop [4]. This is because the population that normally utilizes health care the most are also the most at risk for COVID-19, so their self-quarantine leads to health care visits only when absolutely necessary. Another driving factor of decreased health care usage during this time is insurance. Analysis has demonstrated that private insurance is much more costly now than it has been in previous recessions. A large percentage of privately insured workers have a policy with a deductible >$2,000 (Fig. 1)—a quadruple increase in comparison to a decade prior [4]. In a time where funds are already tight, this further amplifies the tendency to hold off on medical visits for the time being. These changes are further reflected in the overall spending patterns (Fig. 2, 3) per medical service [5]. Figures are included at the end of the article to illustrate these effects.

From the perspective of the health care providers, offices have been experiencing large decreases in use of their services and lack of elective procedures, resulting in significantly reduced revenue. The lost revenue has led to health care workers being furloughed—something seen in many other industries as well—and wage reductions for those who keep their positions.

The health crisis has packed a heavy punch to the overall workforce and, simply put, with less work comes less wages and in turn less spending. Reduced spending then foundationally affects economic stimulation. The moral of the story from an economic standpoint then becomes: the longer this crisis continues, the more difficult it will be to gain traction and begin recovering. As such, it is in everyone’s best interest to prioritize the resolution of the actual health crisis itself [6].

Government intervention has been helpful with the relief bills for citizens and business, but it is already evident that this was not enough to be a sustainable solution. The government lagged with respect to testing efforts, and as a direct result, the economy suffered. Without adequate testing, the strategy of selectively reopening regions has been unsuccessful, as evidenced by multiple states who have experienced secondary surges in case counts leading to re-closure. Had testing been performed more widespread, the reopening of locations may have been sustained.

The overall economic damage elicited by the COVID-induced recession will only get worse the longer the situation lasts. As far as the health care economy goes, there is certainly hope for recovery with time, given historic patterns. This may not be the case for other industries such as entertainment, food, and particularly the small business sector. The effects will certainly linger in the years to come, and the only way to diminish these impacts is by providing intervention and enacting policy now—there is no telling how much longer we can handle this. The concern now entails a critical timeline for when the country is ready and willing to unify to provide the action that is much needed.

[1] Cases in the U.S. | CDC. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

[2] Civilian unemployment rate. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/civilian-unemployment-rate.htm

[3] United States Unemployment Rate | 1948-2020 Data | 2021-2022 Forecast | Calendar. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/unemployment-rate

[4] How have healthcare utilization and spending changed so far during the coronavirus pandemic? – Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-have-healthcare-utilization-and-spending-changed-so-far-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/#item-start

[5] Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan With a General Annual Deductible of $2,000 or More for Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 2009-2019 9335 | KFF. Accessed July 6, 2020. https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2019-summary-of-findings/attachment/figure-f-30/

[6] Cutler D. How Will COVID-19 Affect the Health Care Economy? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(4):e200419-e200419. doi:10.1001/JAMAHEALTHFORUM.2020.0419

Aaron Tran is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Class of 2023. He graduated from Arizona State University in 2018 with a degree in Kinesiology. In his spare time, he enjoys training Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, bodybuilding, playing guitar and piano, and hanging out with his labrador retriever, Rex, outdoors.

For questions, concerns, or discussion: atran13@email.arizona.edu