In my effort to let students learn more about our faculty, staff and, students, I interviewed Dr. David Beyda, the chair of the Department of Bioethics and Medical Humanism at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. The focus of this interview is to discover more about Dr. Beyda and the path he took to becoming a physician, author, and educator.

The Early Years

Lisa Yanez: Where were you born and raised?

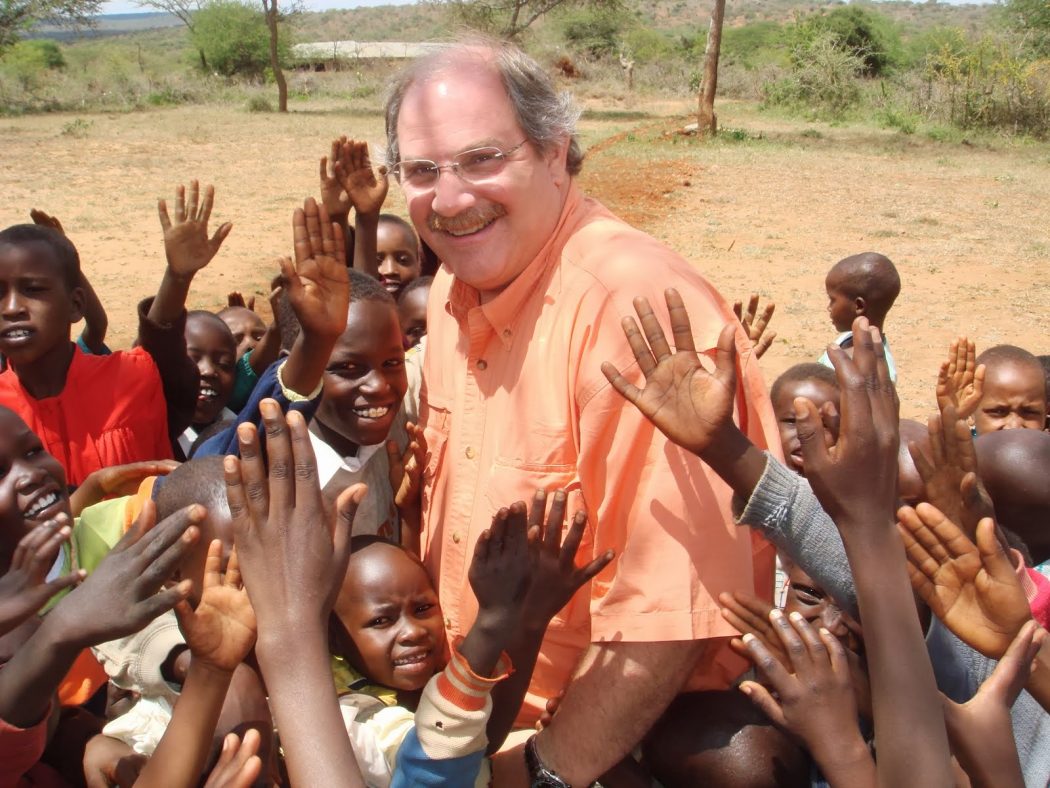

David Beyda: I was born in Washington DC and left the States when I was seven years old and grew up in Mogadishu, Somalia. Then we moved to Tunisia. My father got stationed in Laos. He was with the US Foreign Service, American Embassy. From the time I was seven until the time I was eighteen, I lived overseas. I went to boarding school in Rome, Italy, for high school. Spent the majority of my life, early years in several countries, which is why I am so involved with global health in underprivileged countries . . . I went to Pitt undergrad and got a BS in biology and had a minor in creative writing, English. I was writing at a very early age so to speak. Then I went to Loyola Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago and did my residency in pediatrics at University of Louisville in Kentucky. I did my fellowship in critical care in Johns Hopkins and then came to Phoenix. In 1982, I became one of the founding fathers of Phoenix Children’s and started the Intensive Care Unit and have been here since.

Medical Training

Lisa Yanez: Let’s talk about your path through medicine and then we’ll talk about how you incorporated academic medicine.

David Beyda: My path to medicine started when I was six years old. I kind of always knew I wanted to be a physician. When I moved to Mogadishu, Somalia, when I was seven, I was already thinking about medicine. I would observe people and try to guess what type of illness or disease. At the age of seven, we had a dictionary. There was a picture of the heart, and I would trace it until I could freehand it. My whole path after that lead to my vocation in medicine.

Lisa Yanez: Why did you go to boarding school?

David Beyda: Because my father was stationed in Laos and there was no school there for me to go to. When I was at Mogadishu, Somalia, everything was done by correspondence courses. Our teacher was a woman that was married to another diplomat. She was a teacher back in the States. We would go to her house . . . When I got to Tunisia, we had a “school,” and there were eight of us in my 8th grade class, four boys and four girls. [Of] the four boys, three of us went to boarding school in Rome. The four girls went to Marymount, which is our sister school in Rome. Four times a year, we would all go home. At that time there were two airlines, TWA and Pan American, and both had the same flight numbers 001 went east-west and 002 went west-east. Say we’re going home for Christmas, so December 14th, fifty of us would get on Pan American 001 going east-west from Rome, and that plane would go from Rome to Athens to Istanbul to Pakistan to Karachi to Bombay to Bangkok to Hong Kong, and every time it landed one of us would get off. Two weeks later on Pan Am or TWA 002 west to east, we’d pick everybody up. That was our school bus . . . We grew up very fast—we had to.

Lisa Yanez: What was your path to U of A and then to getting here?

David Beyda: I was division chief and am still division chief of critical care at Phoenix Children’s and have been for thirty-something years. In about 1995, I started writing about the ethical issues in critical care . . . I got invited to be a visiting fellow and a visiting scholar at Georgetown at the Rose Kennedy Institute of Ethics and at the Center for Clinical Bioethics. For about five years, I traveled back and forth every week from PCH to Georgetown. I would leave here on a Wednesday night, red-eye, spend Thursday and Friday at Georgetown, fly back Friday night, and then I would be on call Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday. I did that for five years. I taught at the Kennedy Institute of Ethics and just became an ethicist.

About seven years ago, when Jason Robert was here, he started asking me to do some of the ethics talks that he was giving. He was running the ethics curriculum here before, to bring more of the clinical side in because he as a philosopher. I started doing some of the clinical stuff of ethics. Then when he left, Dr. Chadwick and I met and decided that I should come over and do this. We talked to PCH, and here I am.

Special Moments

Lisa Yanez: What personal moments are you most proud of?

David Beyda: Clearly being married to my wife and having my kids. We’ve been married thirty-five years . . . [Her name is] Charlyce. She’s from Kentucky. We met [when] she was a neo-natal ICU nurse, and I was a senior resident rotating through the NICU . . . that was in October, and [I] kind of fell in love right away. I gave her an order to do something, and she said, “No, I’m not going to do it. It’s not the right thing to do.” I was pretty cocky back then, and I said, “If you’ve guts enough to tell me no, then I guess you’re probably the one.” It’s interesting because we dated from October until the middle of December when I left for Cambodia.

So here’s another story . . . this was in 1979 during that time the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia were killing millions of people in Cambodia. If you go back to my time in Laos when I was a high school student, because of my father’s position, at the age of fifteen, I was able to go and do things in Laos that fifteen-year-olds couldn’t do. For example, I was able to work with a medical group called “Operation Brotherhood,” which was a surgical MASH team, and took care of soldiers and people . . . I flew with Air America, which was the CIA airline of Southeast Asia, and flew with them. That’s how I learned how to fly. I’m a bush pilot. I’ve been flying for forty-something years.

So here’s another story . . . this was in 1979 during that time the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia were killing millions of people in Cambodia. If you go back to my time in Laos when I was a high school student, because of my father’s position, at the age of fifteen, I was able to go and do things in Laos that fifteen-year-olds couldn’t do. For example, I was able to work with a medical group called “Operation Brotherhood,” which was a surgical MASH team, and took care of soldiers and people . . . I flew with Air America, which was the CIA airline of Southeast Asia, and flew with them. That’s how I learned how to fly. I’m a bush pilot. I’ve been flying for forty-something years.

Anyway, I grew up in Laos. I knew Cambodia very well, so in early December in 1979, I got a call from the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees, who said, “We know of you. We’ve heard of your work. We know that you’re experienced. Would mind coming to Khao-I-Dang Refugee Camp in Cambodia and be the medical director for pediatrics? We’re expecting a wave of refugees.” I said, “I had been accepted to be a fellow at Hopkins in critical care already, and I was going to start there in July.” I said, “I’ve got six more months on my residency. I need to talk to my program director.” They said, “We already did.” To make a long story short, I left on Christmas Eve of 1979, and I did my last six months of my residency as an elective in Cambodia as medical director.

[Charlyce] and I dated from October until I left in December. I came back in the June, went right to Hopkins, and then she and I got married in August.Because getting things back and forth was so hard, what I did is I carried around miniature tapes, and every day, I would talk to her on that. I would turn it on when I was seeing patients. I was in a refugee camp. The first day we got there, there was nobody! Within three months, we had 150,000 refugees. She’s got about sixty hours of tape.

Lisa Yanez: You have two sons? What are their names?

David Beyda: Nicholas and Justin. They have both been to Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, etc. Justin is a special-needs adult, and he lives with us. Nicholas is a PharmD academic at the University of Houston, and he married one of our residents.

Professional Moments

Lisa Yanez: Your professional moments. Is there a moment in your head that really sticks out that you’re most proud of?

David Beyda: When Jeffrey’s mom told me that I didn’t know who Jeffrey was. The story goes, I was making rounds, really pompous. I was building a unit, and this kid came in, and he was a mess—every single thing in him was broken. I was making rounds. I had like fifteen people, and I was putting things on the board and talking about physiology and this and that and this and that, and the parents make rounds with us. While I was going to town on this physiology exploration, the mom stopped me and said, “You don’t really know who Jeffrey is, do you? You just know what he is, a bunch of broken pieces that you’re trying to put together again.” “You’re right. You’re right,” and that’s what the book’s about. That is, the who is more important than the what. That’s what covenant medicine is about. The subtitle of book is Being Present When Present, and that is being intentional, being there, and being truly a servant. I think that was the moment.

Lisa Yanez: Does Jeffrey’s mom know the impact that you made?

David Beyda: Probably not. We lost contact. But that’s okay because in the book I write about a lot of stories and a lot of patients and a lot of people. The book centers around one story in particular, and that’s Nicole, a little baby that I spent a week having a tug-of-war with God on. Finally, at the end, I said, “Okay, you win.” I put her in her mom’s arms, took her off life support, and walked out. The grandfather was a reverend at the church that my wife had gone to and as I walked out he said, “David, it’s all about faith.” I walked out, and I didn’t know what that meant for years and years and years. Then the last page of the book, I’ll kind of spoil it for you . . . I learned what faith is all about. That’s where I came in and wrote about prayer at the bedside, and I talked faith and spirituality.

Lisa Yanez: That is so powerful. To switch things up: what do you do to relax? How do find balance?

David Beyda: People ask this all of me, and when I tell them, they kind of look at me like I’m crazy. Writing is a very important part, but I am risk taker. I race cars. I raced Porsches for years, and I was a Porsche instructor. I went to Jim Russell Racing School, Bob Bondurant, Skip Barber Racing. I’ve always driven high-performance vehicles and have raced. I’ve raced at PIR, everywhere.

Reflection and Words of Wisdom

Reflection and Words of Wisdom

Lisa Yanez: Given the chance what would you say to your 28-year-old self? Or any advice that you would pass along if you were in medical school?

David Beyda: I’ll tell you what I told my son at 28. I said, “You know what you want to do, so just do it. If you’ve got a big dream, all I ask of you is to make sure that you make it happen.” I think there’s just lots of things that are put before us that if we spend too much time questioning it, then it defeats the whole purpose of why it was put in front of us. You either accept it or you turn around and walk away.

Lisa Yanez: Are there any final thoughts or a favorite quote?

David Beyda: A final thought is in life, all relationships are centered on this whole aspect of being present when present. If you’re not present when present, then it’s a superficial relationship that is disingenuous—it means nothing. That it shouldn’t even be. That if you’re going to have an interaction, relationship, you should hold it to its highest standard.

Lisa Yanez is the Assistant Director, Curricular Programs in the Department of Academic Affairs at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. She earned her Master of Business Administration degree at Roosevelt University in Chicago, Illinois. Lisa successfully defended her dissertation recently and will graduate in May 2017 with a Doctor of Education at Arizona State University. Her dissertation research focused on active engagement in medical education.