During one of my first days shadowing my Community Clinical Experience (CCE) preceptor, I had the opportunity to observe a pelvic exam. This was not the first pelvic exam I had watched – my preceptor is an OB/GYN, so she performs several during a typical day in clinic.

This pelvic exam was a bit different from the previous ones I’d observed, though. Before seeing the patient, my preceptor told me she doubted I would be allowed in the room – the last time my preceptor had seen her, this particular patient had a panic attack during the pelvic exam. However, to both my preceptor’s and my surprise, the patient told the medical assistant that she would be okay with a student observer.

Inside the room, my preceptor and I were greeted by a composed and candid young woman. While going over her medical history, she mentioned that she was in therapy for PTSD, and acknowledged that this was part of the reason she’d had a panic attack during her last visit with my preceptor. She laughed a bit – perhaps self-deprecatingly or perhaps to just diffuse some of her discomfort – when talking about her mental health history. Though it was never directly stated, my preceptor’s comments outside the room and the details that came up during the interview suggested to me a history of sexual abuse.

As my preceptor transitioned from the patient interview to the pelvic exam, she gave the patient the choice of either having me leave the room or staying for moral support, perhaps giving her a hand to hold during the exam. It was obvious to both my preceptor and me that the patient was nervous about the pelvic exam, and I was more than ready to leave the room if there was a chance it would make the process marginally more comfortable for her.

Surprising to both of us yet again, the patient said she would like me to stay. During all the other pelvic exams I had observed earlier that day, I stood behind my preceptor, trying to appreciate the cervix and other anatomy that can be seen during these exams. With this patient, I instead stood at the head of the patient’s bed, wanting to make my hands available for her to hold if she would like. However, the patient kept her hands tightly clasped over her stomach. It was very evident that the exam was deeply uncomfortable for her – she seemed to be holding back tears throughout the whole process. My preceptor and I did our best to try to distract her. I complimented a bracelet she was wearing and my preceptor told her about a birth we’d attended earlier. The exam was finished relatively quickly, and the patient thanked us as we left the room, seeming a bit shaken but still mostly composed. I don’t think she shed any tears while we were in the room with her, but after the door closed behind us, we could hear her sobbing.

This experience was one of many times during my first year of medical school when I’ve wondered where the line is between acceptable and unacceptable patient discomfort. In our doctoring course, we are taught communication strategies and a number of other skills that are intended to best enhance a patient’s comfort and trust in us while we take a medical history and perform a physical exam. During the past year, I’ve learned to warn patients before asking more personal questions about their risk behaviors related to recreational drug use and sexual history. I’ve been reminded to cover my patient’s feet with a drape during the supine parts of the physical exam (the drape is primarily intended to preserve the patient’s modesty but can also be used to keep bare feet from getting cold). We practice “talking before touching,” telling a patient where we’ll be placing our hands and stethoscopes before we actually do anything. And we make sure to say things like “I’m going to check a pulse in your neck now” instead of “I’m going to feel a pulse in your neck now” because the word “feel” can have unpleasant connotations for many patients.

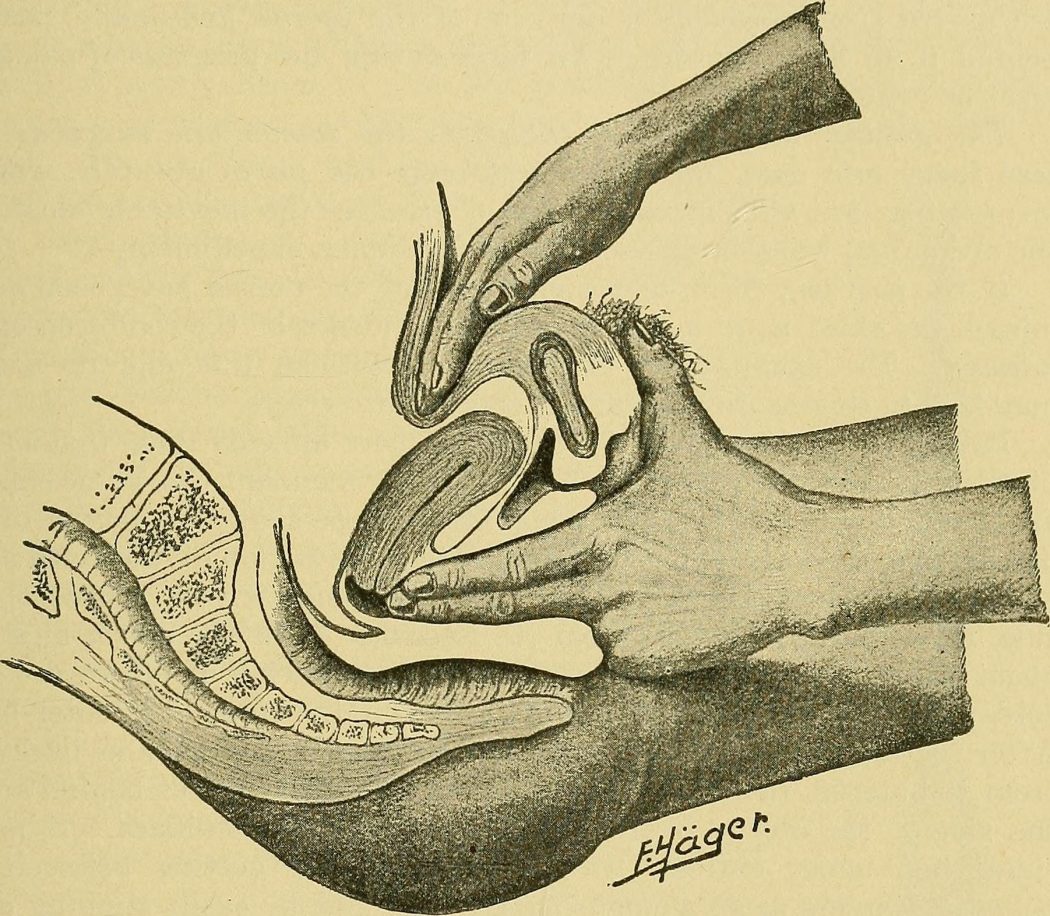

At the same time, however, we are taught a lot of maneuvers that cannot be done without causing patients discomfort or pain. For example, if a patient has tenderness in the right lower quadrant of their abdomen, one of the tests we are taught to do involves applying deep pressure in that area. If the pain is worst when the pressure is removed, a phenomenon known as “rebound tenderness”, there is a high probability that the patient has peritonitis. This is not the only skill that we are taught that has a reasonable chance of causing patient discomfort – assessing the diameter of the abdominal aorta or testing for an abdominal jugular reflex also both require uncomfortably deep and prolonged pressure on a patient’s abdomen. Even though we drape our patients when not examining particular aspects of their body, certain parts of the physical exam, like listening to the heart and lungs, work best when the stethoscope can be placed directly on the patient’s skin. This can only be done by asking a patient to move clothing or hospital gowns out of the way. Pelvic and rectal exams are physically uncomfortable for many patients, painful for some, and almost invariably not something that patients look forward to when they go in to see their doctors.

As medical students, we are thus simultaneously (and perhaps paradoxically) taught that patient comfort is tantamount, but that it is inevitable that we will also end up doing things that will make our patients deeply uncomfortable. When – and why – do we decide that a patient’s discomfort is acceptable?

The question of when it is appropriate to actively make our patients uncomfortable is a fundamentally moral question. One of the foundational principles of medical ethics, non-maleficence (the tenet of “doing no harm”) sits at the heart of this question. You could argue that doing something that hurts patients violates the principle of non-maleficence. However, well beyond the elements of the patient history and physical exam that I’ve been exposed to as a first-year medical student, modern medicine frequently involves using diagnostic tools and treatments that are actively harmful to patients. CT scans and X-rays both expose patients to ionizing radiation. Many chemotherapy agents invariably cause a multitude of side effects because they tend be just as poisonous to certain types of healthy, normally functioning cells as they are to the cancer cells they’re trying to target. Organ transplants can extend patient survival at the cost of lifelong immunosuppression and thus all of the risks of infection that come from having a compromised immune system.

Therefore, it seems that both healthcare providers and patients have accepted that there are circumstances where the potential discomforts and harms associated with certain medical procedures are outweighed by potential benefits. Testing for rebound tenderness is worth it if it helps to diagnose a patient with peritonitis. Chemotherapy or an organ transplant is worth it if it can extend length and quality of life. Pelvic exams are worth it if they can help to identify cancer or infectionsa. Medicine is often a game of risk and benefit analysis. We accept that we must sometimes do things that harm our patients on some level under the assumption that the potential for good outweighs the potential for harm. This makes a strong moral argument for the importance of evidence-based medicine. It also tells us that, to the best of our ability, we must make decisions about when potential benefits will outweigh potential harms in collaboration with our patients. After all, what constitutes “acceptable risk” and what sort of odds are thought to be reasonable depend on a patient’s personal set of values and priorities. We therefore need to help patients understand the risks associated with particular diagnostic processes and treatments, as well as trust our patients to know when they are willing to accept the risk of discomfort, pain, or worse for the sake of some potential benefit.

It seemed to me that the patient I saw with my clinical preceptor had a lot more reason than most other patients to want to avoid the discomfort associated with a pelvic exam. I didn’t get to know her well enough to know what her values were, or why she decided having the exam done was worth the emotional pain I witnessed. I will never know whether the tears we overheard after the encounter were simply a means of emotional release or if the pelvic exam was yet another traumatizing experience. I do know that she decided to come in for her scheduled appointment and that she consented to my being in the room to observe. While I’m sure I will always worry about my patients and the discomforts I will (sometimes routinely) put them through, I also need to trust their judgment and do my best to ensure that the care they look to me to provide helps them nonetheless.

[a]Notably, several professional societies and other organizations have recently called into question the effectiveness of annual pelvic exams in asymptomatic, non-pregnant patients. A 2018 Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) indicates that “data from [a limited number of studies [that] have evaluated the benefits and harms of a screening pelvic examination] are inadequate to support a recommendation for or against performing a routine screening pelvic examination among asymptomatic, nonpregnant women who are not at increased risk of any specific gynecologic condition [1].”

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 754: The Utility of and Indications for Routine Pelvic Examination. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(4). https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2018/10000/ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__754__The_Utility_of_and.60.aspx.

Michelle Arnold is member of the The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Class of 2022. She received her Bachelor’s degrees in Biochemistry and Spanish from Arizona State University in 2015 and a Master’s degree in Applied Ethics and the Professions (Biomedical and Health Ethics) also from Arizona State University in 2017. She has interests in medical humanities, patient-provider relationships, and improving healthcare for underserved communities.