Growing up, I never planned to become a physician. As a relatively healthy child, I assumed all doctors were functionally the same as the one I visited for a yearly checkup or for the occasional cough. However, in transitioning from a career in documentary filmmaking to now having an entire year of medical school behind me, I’ve been impertinently introduced to the competitive world of medical subspecialties.

“What type of doctor?” is the interminably repeated question asked of medical students by healthcare providers and laypeople alike. More often than not, answers such as “something procedural” and “surgical subspecialty” receive laudatory nods while a response of family medicine elicits dismissiveness or even vociferous remonstration: “Isn’t that all diabetes and hypertension?” “If you like family medicine, just become a nurse practitioner.” “You won’t make any money.” “I guess it makes sense if you want time to raise a family.”

Coming from an equally male-dominated career in the film industry, it is difficult not to hear, “You are a low-achieving female choosing the path of least resistance.”

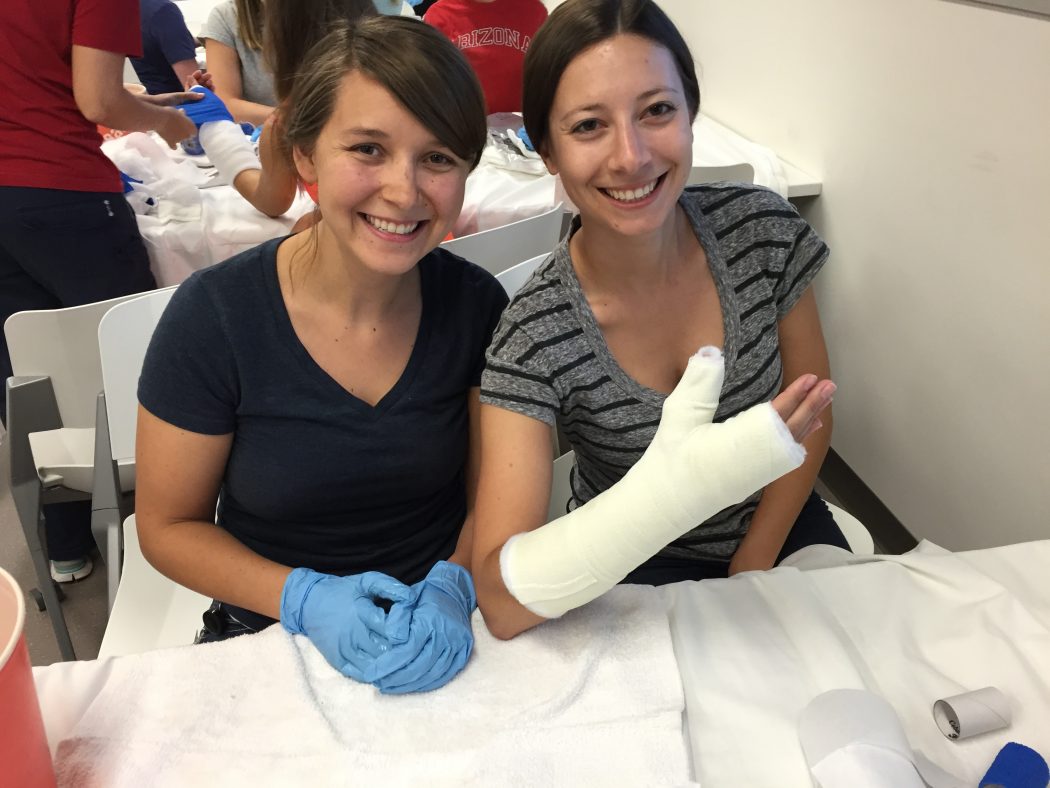

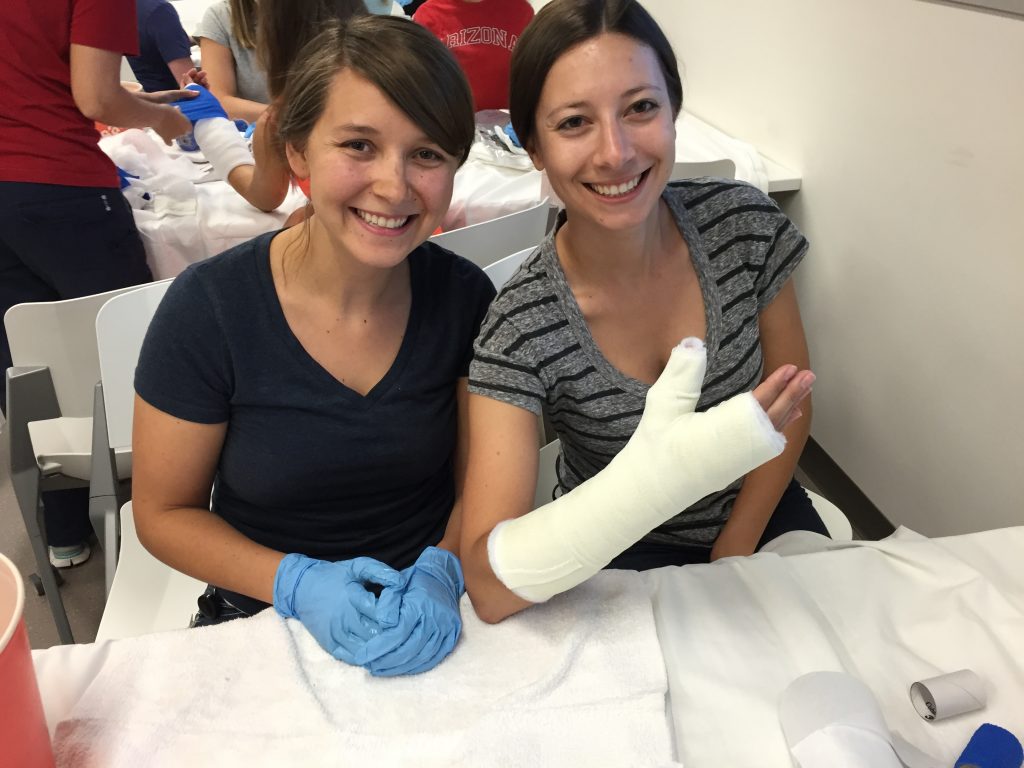

Casting Clinic hosted by the Family Medicine Interest Group

This is not a vehement takedown of specialists. The advancement of medicine requires physician-scientists who understand rare and complex disease patterns, have the skills to perform high-risk surgeries, and pioneer new treatments for existing and emerging pathology. However, it is problematic when often only those who produce immediate outcomes are viewed as successful physicians. A family physician might manage a patient’s blood pressure for 10 years, prolonging his or her life and improving its quality, but longitudinal prevention of heart disease is not as tangible an outcome as a CABG or valve replacement.

Why are primary care professions judged so harshly? Many argue that these fields are unattractive due to long hours and “low” pay. Others opine that family physicians do not receive enough training to treat serious illnesses. What isn’t discussed as publicly is the desire for the prestige inherently involved in choosing a specialty. After spending a decade in training, competing against the brightest and most resolute colleagues, striving to constantly prove our intelligence and capabilities, it is not surprising that most medical students choose specialties associated with esteem and notoriety. A study of undergraduate premed students at the University of Pennsylvania mentioned that “there [are] no primary care physicians depicted in current television, which tended to minimize the exposure of the field” [1]. Surely, we can all agree that cardiothoracic surgery sounds much sexier than monitoring an A1C. Yet, with the adoption of the Affordable Care Act giving more Americans access to health insurance than ever before, monitoring an A1C is likely one of the most vital roles a future physician can employ [2].

When volunteering at the Wesley Health Center in Phoenix, I am consistently reminded of the importance of family practitioners as intermediaries between patients and our unwieldy healthcare system. I have seen cases that are complex and require layers of coordination, lifestyle counseling and preventative care, such as a landscaper with chronic shoulder pain from carrying a leaf blower for 6 hours a day. He can’t leave his job because it is his family’s solitary source of income. An MRI is cost-prohibitive, leaving us unable to discern the severity of the damage. He has brought with him a bag full of medications to be reconciled: he has diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and allergies. He reluctantly pulls up his pant leg to reveal a rash that he reports is getting worse.

There is no easy fix. One might survey this patient and say, “refer to orthopedics, cardiology, urology and dermatology,” but many patients don’t have the time, insurance or resources to visit an entire suite of complementary providers. In medical school, we are reminded again and again that heart disease and diabetes are among the leading causes of death in this country. If this is what America is suffering from, shouldn’t we, as future doctors, be eager to take on these challenges and give our patients the comprehensive care they so profoundly require?

What can we do to rebrand primary care so that it garners the same respect as other medical specialties, as it does in many other countries? Incentivizations in the form of loan repayment options are often touted, as are changes in reimbursements. Some studies have shown, however, that even a pay raise would not convince students to choose primary care [3].

Medical schools should begin by recognizing the factors that discourage students from entering these professions. Giving students the opportunity to experience the breadth of primary care, not only in clinics but also in hospitals and procedural contexts, could help clarify the varied settings where these doctors can practice. Dr. Steven Lin, a Family Physician from Stanford University, suggests incorporating strategies in the first two years of medical school, before students have a strong sense of the field they’ll choose [4]. Dr. Lin contends that surrounding students with primary care role models who speak highly of their profession will help students to feel they can relate to a particular physician. Compelling family doctors to more readily share their stories is an inexpensive mechanism to motivate students to follow a similar path.

I have not yet decided what path I will choose in medicine, but if family medicine is my choice, I am hopeful that I will receive the same level of respect as my colleagues who enter subspecialties. And as far as the argument that primary care doctors earn less money, a wise colleague once said, “I’ve never seen a doctor in line at the soup kitchen.”

- Gold J, Barg F, Margo K. Undergraduate Students’ Perspective on Primary Care. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2014; 5(4); 279-283.

- Smith SR. A Recipe for Medical Schools to Produce Primary Care Physicians. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:496-497 .

- Erikson C, Danish S, Carle A. The Role of Medical School Culture in Primary Care Career Choice. Acad Med. 2013; 88(12); 1919-1926. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038

- Chan VT, Lin SY. Renewing US medical students’ interest in primary care: bridging the role model gap. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:1-2 doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131802

Michelle Blumenschine is a medical student in the Class of 2018. She holds degrees in film & TV production and journalism & mass communication from New York University and completed her pre-med post-bac certificate at Columbia University. Before moving to Phoenix from New York City, Michelle worked as a documentary film producer. She enjoys making to-do lists, drinking craft beer, and collecting National Geographic magazines. She is pursuing a career in obstetrics and gynecology.