This past month I spent the majority of my time reviewing charts of patients who had sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI) as part of a research project. In reading each patient’s story, I often found myself thinking of the moment in time that exists between the before and after of when trauma occurs. An infinitesimal amount of seconds, too small for us to even comprehend, and yet that fraction of time holds such significant weight. An instant that marks the transition from normal day-to-day life, to a life that has been irrevocably changed, often without any warning. A complete blindside.

A TBI is defined as an injury to the brain caused by an outside force, which may include a forceful bump, blow, or jolt to the head and/or body, or from an object entering the brain.1 Many of the cases I read were from car or motorcycle accidents, some from gunshot wounds or assault, and others were pedestrians who were struck by vehicles. I can picture what it might feel like to be in that moment; a sudden jolt that violently throws me, a cacophonic screech of metal grinding against metal, glass shattering, the world flipping, a surge of pain and then….

I won’t pretend to know what patients experience afterwards as the blare of sirens fills the air, flashing red and blue lights blur through the streets, harsh bright fluorescents glare down and unfamiliar faces clad in blue and green crowd around them. Are these patients partially aware of what’s happening? Do they go elsewhere to some in-between space, or a memory buried deep in their mind? Or is it all just an indefinite stretch of black?

Around them, it’s a rush. Rush of the first responders to the scene, rush as the ambulance screams down the street, rush into the trauma bay, then to the scanner, then to the operating table and then, finally, everything slows, and they are wheeled back to recovery. And this, I think, is when the hard work for the patient really begins.

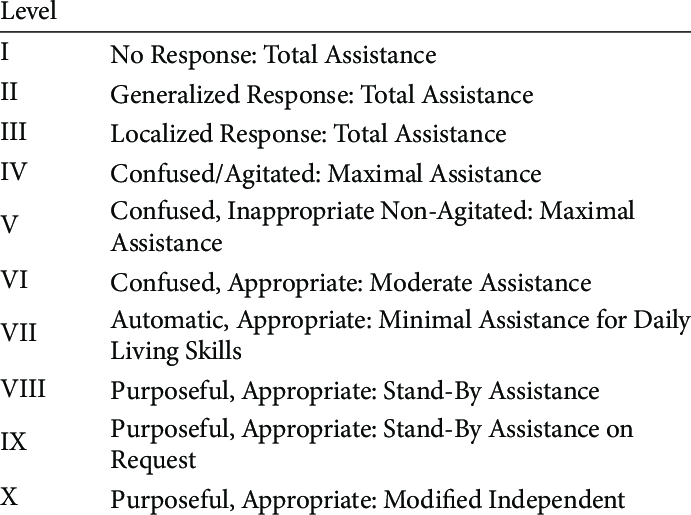

The recovery process from a TBI consists of ten levels as defined by the Ranchos Scale, originally created by the head-injury team at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey, California.2 The Ranchos Scale is often used in conjunction with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) during both the initial assessment and throughout the recovery period. Each level takes into consideration both the patient’s level of consciousness and how much they must rely on assistance to carry out cognitive and physical tasks.2

The Ranchos Scale

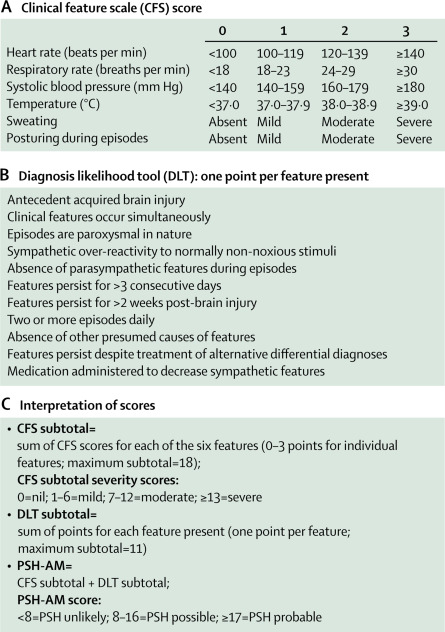

In the earlier stages of the recovery process from a TBI, paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity (PSH), otherwise known as neurostorming, has been recorded to occur in up to 80% of patients.3 Neurostorming, in the most basic sense, is the body’s fight-or-flight response on hyperdrive. The current thought is that a severe injury to the brain causes a disconnect, and the sympathetic nervous system that regulates the stress response becomes overactive in an effort to protect the brain and body from further damage. Unfortunately, the counteractive parasympathetics are also damaged from the trauma and cannot downregulate this excitatory response. This results in paroxysmal tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hyperthermia, and decerebrate posturing, which may last hours to days, but can be intermittent for months of the recovery period.4

It’s as if the patient’s brain is caught in a prolonged state of stress, desperately trying to prepare and protect the body from an injury that has already occurred and cannot be undone. The brain still believes it’s being traumatized, and I can only imagine that for the patient, they are trapped in a perpetual state of fear. Current pharmaceutical therapies are limited to mitigation of the sympathetic responses, along with avoidance of any triggers and managing the other organ systems affected.3 These therapies can only address the physical manifestations of neurostorming though, not the constant mental and emotional battle the patient must endure.

The PSH Assessment Measure

Having a glimpse at the stories of these TBI patients has given me a new perspective on what it means for a patient to be “stable” or “safe”. From an outsider’s point of view, yes, vitals are stable and they’ve made it through the life-saving surgery and they are no longer actively dying in front of you. But in their mind, we can’t begin to imagine what must be going on, what they are experiencing or what they are feeling. It really gives a new meaning to the quote “be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about.”

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

- Lin, Katherine, and Michael Wroten. “Ranchos Los Amigos.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2024. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448151/.

- Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity: the storm after acute brain injury. Meyfroidt, Geert et al. The Lancet Neurology, Volume 16, Issue 9, 721 – 729

- Neurostorming In Severe Brain Injury Patients | Nexus. 16 Dec. 2019, https://nexushealthsystems.com/neurostorming-in-severe-brain-injury-patients/.

Kathleen LeFiles is a medical student from the Class of 2026 at The University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix. She graduated in 2020 from The University of Arizona in Tucson with a degree in Physiology and a minor in Care, Health, and Society. When she's not studying or writing, Kathleen enjoys practicing Pilates and yoga, frequenting local coffee shops, and listening to pop music. Feel free to contact her @kathleenlefiles on Instagram or email at klefiles@arizona.edu.